Camouflage

These Gorgeous Prison Walls

For many years—indeed, for the better part of my life—I have (oftentimes and for years, successfully; other times less so) attempted to ascribe truth and meaning and reasons to live to art, to poetry, to story, to song, to music; each attempt (some, as I said, lasting years) heartfelt but in the end, in the unforgiving light of truth, proving contrived and false, leaving me with the sense that on some deeper level, I have just wasted even more time.

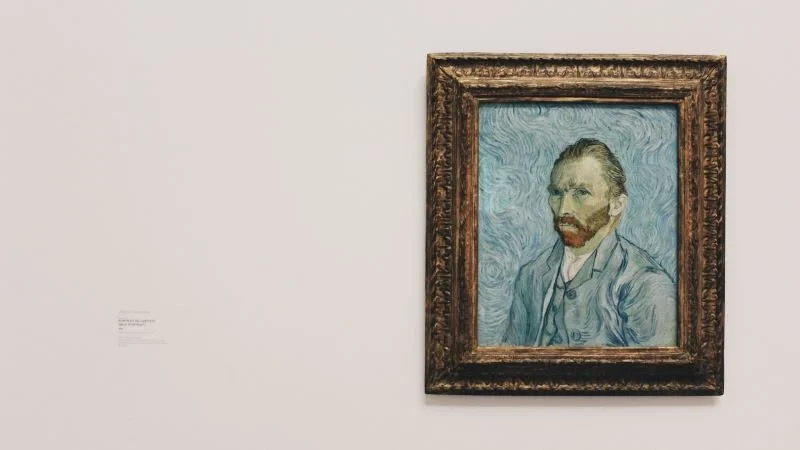

For deeply at heart, I have always, in the end, recognized these attempts as a self-trickery I refused to acknowledge, glossing over the disturbing feeling that, in truth, there was nothing there but pretty clothes for the emperor, a pleasing camouflage (decorating the prison).

Today, it rises as truer and truer that neither music nor literature ultimately matters; song does not matter, story does not matter. Relatively, yes, of course they matter, but ultimately, no. The only thing that matters is clearly seeing. Everything else, no matter how beautiful, is simply interfering with the clear view, a view that we must maintain, steady and true, in order to solve the earthly life-and-death puzzle that we find ourselves very much an integral part of.

Ultimately—admittedly as ultimately as things go—the arts, these spiritual purposes and pleasures, are simply jail decorations: the nice and cheerful coats of paint on these cell walls are simply camouflage.

This realization, mind you, from someone who most of his life has subscribed to Friedrich Nietzsche’s view that “without music, life would be a mistake.”

From someone who most of his life has revered classical music, feeling that listening to it, and understanding it, was a holy act bringing me closer to God. For most of my life, I have seen the classical composers, especially Bach and Beethoven (and also Handel, though he was more of a commercial genius-slash-wonder, as was Haydn), as Gods personified: Bach with his glorious mathematics, Beethoven with his many continents of amazement.

But when we arrive at the end of the day, all that really matters is seeing things clearly, and that takes looking. And when it comes to truly looking, art—much like sex and drugs and good food—for all its professed and actual wonders, does get in the way.

For in the stillness of clear seeing, there is no art, no music, no stories: there is only the clear seeing.

It is true that a sweeping symphony gifts you with spiritual wings, the better to fly, and that heartfelt poetry, like that of Joni Mitchell’s, say, or of Denise Levertov’s, takes you by the hand and opens many a door. Still, you have to do the flying, the walking, and this is best done alone in silence, unencumbered by beauty.

It is also true that some current music (Imogen Heap would be a good example) is so wonderful and so amazing and uplifting that one cannot but wonder at the incredible vision and creativity of the spirit. So wonderful that one can easily contemplate living a life with this alone as sustenance.

So magical—think Les Mystere Des Voix Bulgares—that what else could possibly be as fulfilling?

But ultimately, as with everything else, even this wonder is fleeting and eventually fades. The wonder of it evaporates, and one is left with the need, the desire to find new and more of this to again stir and lift.

It is this desire, this thirst for beauty, this need (as much as anything else) that gets in the way of seeing things clearly.

For what is music but pleasant sounds; what is art but pleasant sights; what is story but pleasant thoughts conveyed in a captivating voice or by inky letters?

Still, I cannot deny that I have often sought the hidden message, the shrouded truth in these wall paintings, these transports. But then I’d find that the looking for the hidden message was the message and that this message always was the only message there.

Have they then, in my view, no purpose? Art? Music? Story?

Yes, they do. On a relative and very relevant level, they do. Of course, they do. Two purposes: To stir. To steer.

I believe that these cave paintings (cell decorations) can, if created with correct and ethical intention, serve to stir the sleeper, to shake him or her slightly, gently, prodding eyes open. And I say with correct and ethical intention advisedly, for the vast majority of art (and music and literature) today does not delightfully instruct (which was once the purpose and definition of good literature); rather, it degrades and spins in an out-of-control effort to make and grab as much attention and money as possible.

However, given correct and ethical intention, art, song, and story can indeed stir awake, prod sleepy eyes open. Gender a seeker.

I know. I have been gendered a seeker.

After which, the second purpose comes into vital play: to steer this seeker; to steer the gendered seeker in the only direction that will raise for her or him the one true sun, heralding the dawn of self-discovery.

::

For me, these days, what helps me see more clearly is not art per se, but the shared wisdom of those wise men and women who have gone before me.

I turn to Zen; I turn to Vedanta Advaita; I turn to those current teachers who have walked the path farther than I have—B. Alan Wallace (who has produced a small library of excellent books, primarily on Tibetan Buddhism) and Burgs (whose “The Flavour of Liberation” books are wonderful) come to mind—and I sit by their virtual feet, eyes and ears wide open.

In my experience, some teachers speak better to some than to others.

I have studied many of them only to discard them. Others, I return to time and again, and those I stay with. They help keep my eyes open, keep me searching and seeing.

And to back this up, this strange and definitely unconventional, and most likely hard-to-accept take on the arts, I look at phenomena like The Beatles, I look to true artists like Joni Mitchell, to composers like Bach and Haydn, and I draw the inevitable conclusion that for all the beauty poured forth by Joni Mitchell, for all the world-wide appeal of The Beatles, the world is actually not a better place for it.

Ephemerally, internal worlds of those who listen become a better place, but only ephemerally, once the song is over, once the poem is read, and once the outside world with its demands and hungers reconquer that internal territory, beauty is forgotten and need (and greed) again rules the world.

The arts offer a reprieve, that is all. And if that reprieve grows too long if it lasts, say, an entire lifetime, well, then no looking will have been done, no opportunity of clearly seeing will have been seized. That is a life wasted.

If this life is a prison of sorts, which I don’t think is too wide off the mark, then the key to the prison lock is clear seeing; seeing things as they really are beneath all that glitter, beneath all that suffering, beneath all that camouflage. The key is seeing beyond the apparent, seeing through the beauty, seeing the underlying and ultimate truth.

::